Case Study: Timeline of the rehabilitation and integration of a captive parakeet into the wild

Devna Arora

On the rescue and admission of any animal, it is important that a protocol and a timeline of rehabilitation be established in order to plan a timely release. Although parakeets are typically rescued and rehabilitated in sufficiently large numbers, this document aims to give you an idea of the time required for an adult parakeet that has lived its life as a captive bird, to regain its strength and be able to fly in free skies.

History and condition on admission

Mithoo was a 6 year old Rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri) that had been found as a fledgling and picked, caged, and passed on to another family in the following months. For six years of his life, he lived in a cage (which was now rusty) that was 1 foot x 1 ½ feet and just barely over a foot high. His tail feathers scraped the bottom of the cage and every time he moved left or right, his head would bang into a large swing that was placed centrally above his perch (as seen in the pic above) – he never used the swing. His cage was kept on the balcony floor where the house dog would road around him causing further stress. To top it all, he was put under the shower once a week since they were told that parakeets love water – this perhaps led to his initial negative association with water.

He was never exposed to other birds or wild parakeets except for the crows that would occasionally attack him – if a family member was present, the crows would be shooed away. Fortunately there was little interaction between him and the family and he hadn’t been tamed. He would reluctantly accept food by hand and did not talk, acknowledge or return any interaction towards him. In my experience and observations of other captive parakeets, the levels of stress were extremely high in this bird and the will or joy of living was extremely and unusually low. The only thing that made him happy was when he was left alone.

Physically he was in poor health – his muscles had weakened over time, his wings had never been exercised in his life, and his lung capacity was negligible. He couldn’t even scream out like a normal parakeet without running out of breath. His voice was hoarse when he attempted to call and even half a call in the lowest pitch took the life out of him where he had to visibly pant for breath before attempting another call. Far from being able to fly, he would struggle to even move on his new perch and was much too scared to even climb or descend perches initially. Parakeets are normally adept at climbing connected braches and grilled cages but he was very reluctant and struggled to do so.

Fortunately, there was no intentional abuse. His feathers were intact and he had never been physically handled. All he needed was to regain his sense of being a wild bird and the strength and the will to live free which was completely absent in him in the beginning. Thankfully for him, on the insistence of their children, the family decided to give him up for rehabilitation so he could be set free.

Protocol for rehabilitation

The very first task was to get him to come out of the cage and move around the enclosure confidently enough. With exercise and movement, his muscles would gradually develop. Food was used as driving force to encourage movement. I always ensure he had the basics available next to him but made him step further for treats. For example, there was always a bowl of seed and fresh water accessible but if he wanted fresh groundnuts, he had to move further to obtain them. This worked well.

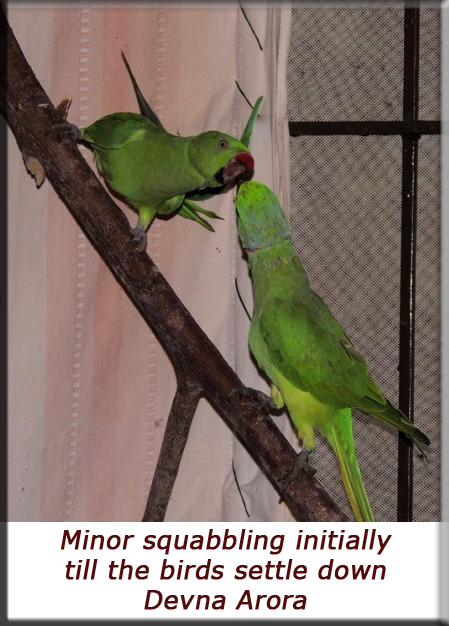

He was rehabilitated with two younger parakeets and introduced to them gradually over a period of two days. He was initially terrified of them and wanted to attack every time either of them approached him. So they were only initially allowed to meet through the bars so each was a safe distance from the other. Once the novelty and obsession had reduced, he was encouraged into the enclosure with the other two birds. Although they squabbled a bit initially, the birds all settled down very well in a couple of days. The younger and stronger bird would in fact protect him and keep an eye on him to ensure he was safe and unharmed. On the two initial instances during his flight practice that Mithoo fell to the ground and felt too dejected and scared to find his way back, the younger bird walked up to him and led him back to the perch.

He was given his own time and space for the first month as I was afraid that pushing him beyond his abilities would only result in a muscle pull. It was after the first month when he showed signs of being ready that I pushed him to reach his abilities and encouraged flight practice – this had to be done gently without causing panic and distress. I would gently approach him from one side of the room which would encourage him to take off in the opposite direction; at this point I would completely back off and give him the space to return to the perch. This exercise was a little frightening for him initially and it would leave him breathless and a little scared but as his capacity increased and he was able to take bigger rounds, he started enjoying the process, needed little encouragement and took longer and successive rounds all on his own like the younger birds.

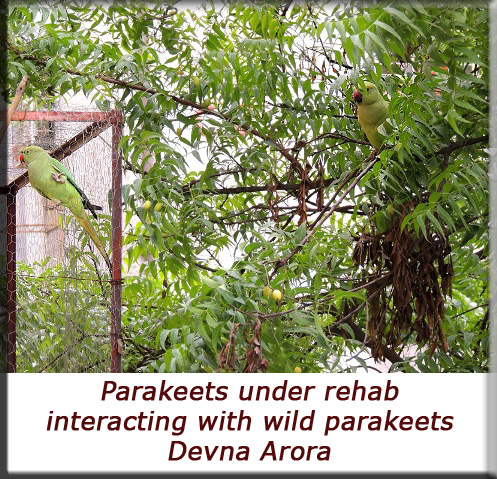

Their enclosure attracted wild parakeets that would visit and watch the birds often. Although Mithoo never showed great interest in the wild birds initially, he soon copied the younger birds and chattered loudly and communicated with the wild birds every evening.

He had been kept on a diet of guava and apple and some seed. Although not as curious as the younger parakeets, he accepted new foods gradually. He relished fresh groundnuts (his beak was strong and he enjoyed shelling them) and enjoyed corn on the cob, fresh peas in the pod and various types of beans particularly String beans. He also enjoyed strips of multigrain bread which were given to them as treats.

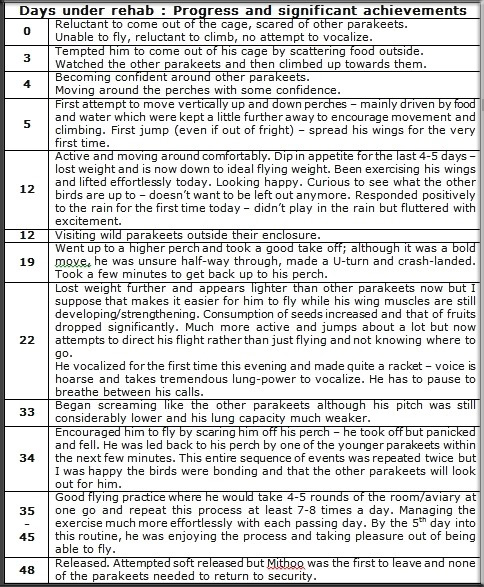

Timeline

Considerations for release

Mithoo was absolutely pushed to his limits and released after 7 weeks of rehabilitation. He was released with a group of younger birds and I expected for them to main a fluid group for a few weeks after release but they all spit up and headed in individual directions. Although he survived very well and was seen and easily identified for a month after release, I feel the transition would have been easier for him if he was given another two weeks of care.

Over a period of time, all older birds/animals tend to get accustomed to the way of life they have been used to. Breaking this pattern is one of the biggest challenges faced initially. In his case, he benefitted significantly from the enthusiasm and curiosity of the younger birds. The younger birds were full of life, always joyful and always up to something. This brought tremendous positive energy for Mithoo, encouraging him to want to be free and happy. He picked up on happy behaviours from them.

There are far too many captive parakeets in the country, most of them being wild caught and extremely tame. Tameness and attachment to humans will of course be a major consideration when rehabilitating a bird and so is age. Wild parakeets live well over 20 years of age (longer in captivity) and most birds under the age of 10 years certainly have a good chance at a successful release but each bird must be handled on a case-by-case basis depending upon its history and condition upon admission.

Again, for birds that are admitted in physically damaged conditions – plucked feathers, damaged muscles or other infections and ailments (mostly all caused due to bad handling and negligent husbandry practices), the timeline towards appropriate rehabilitation and release will of course be contingent upon full recovery.

Case Study published in 2014.