Hand-rearing barbets, Megalaimidae sp. continued

Devna Arora

Link to Page 1: general guidelines

Stage-wise care of barbet chicks

Stage 1: Nestling – unfeathered

Characteristics: Barbet chicks are born completely naked with their eyes closed and are completely dependent on their parents for warmth, food and care. Thermoregulation is poorly developed in new-born chicks and they need an external source of heat at all times. The chicks’ eyes open by the end of the first week. At the same time, the first pin feathers begin to erupt. Pin feathers rapidly erupt in the second week of the chick’s life and the chick is fairly feathered by the end of the second week.

Feed: The chicks are extremely delicate at this stage and must only be fed on soft and very easily digestible foods. Soft boiled egg, fish protein and fish eggs must together make up roughly 50% of the chick’s diet for the first couple of weeks. The remaining 50% can comprise of primarily banana and some chiku, melon and figs. Infant cereal too may be added to the diet if required but is unnecessary and perhaps best avoided. The foods must be skinned and pureed or blended in a mixer and fed to the chicks with the help of a syringe. A blend of egg, fish and/or fish eggs may be made for the entire day and refrigerated but fresh fruits must be added to every meal. I prefer giving the chicks a 50:50 mix of fruit and protein in each feed. The feed may be diluted a wee bit in the first week by adding fresh squeezed fruit juices – grapes and pomegranates are excellent for the purpose.

Once the chicks have settled and are accepting the feed well, ¼ drop of vitamin and calcium drops must be added to at least 2 feeds a day to begin with and gradually increasing to ¼ drop in four feeds of the day by the end of the second week. Probiotic supplements too may be added as per the chick’s requirements – a tiny pinch of powder added to 3-4 feeds should be adequate for a chick at this age.

The chicks do not require any additional water at this stage as they get the required amount through their feed. [Please refer to note on ‘Water and Hydration in the previous page for further details.]

Feeding quantity and frequency: Feeding must begin at about 6 am and continued till about 7 pm. The chicks must be fed every half hour in their first week of life and every 40-45 minutes in their second week of life.

A new-born chick may only have 0.1 ml of formula per feed, increasing to 0.2 ml of formula per feed by the end of the first week. The feed quantity would gradually increase to 0.5 ml of formula per feed by the end of the second week. Once the chick has had enough, it will cease to beg and must then be fed at the next feed. Over-feeding must always be avoided.

As a rough estimate, a chick will consume 2-3 ml of feed a day at birth and up to 4-5 ml of feed per day by the end of the first week. The daily average of feed consumed would increase to 8-10 ml by the end of the second week.

Special care: Naked nestlings require additional warmth throughout the day even when housed at room temperatures. The surrounding temperature must be maintained at approximately 104˚F – 106˚F for the first week and reduced to approximately 102˚F – 104˚F in the second week of the chick’s life.

As their skin is very tender, they must be kept on soft bedding – a lining of soft cotton cloth may be preferable to paper towels at this stage. Refrain from using fleece or cotton towels.

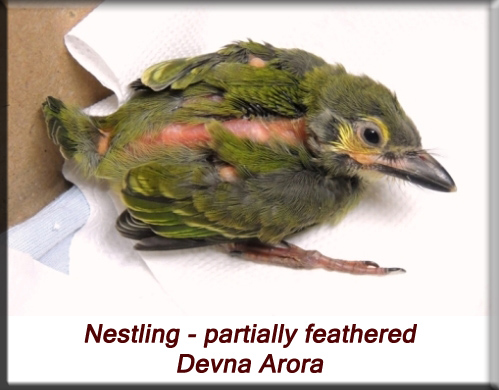

Stage 2: Nestling – feathered

Characteristics: The chicks are adequately feathered, covering the bulk of the body, at this stage. Colour markings which are indicative of the species, become prominent at this stage. Chicks develop rather quickly now and will be ready to attempt short flights in another week to ten days. The chicks are quite active and strong by this stage and begin standing on their legs by the fourth week of their lives.

Feed: The chicks are given a similar diet but the food proportions vary. At this stage, I would reduce protein content (fish, eggs, caviar) to about 25% of the chick’s diet, reduce bananas to roughly 25% of the diet and increase other fruits like chiku, melon and figs to 50%. Formula must nonetheless be pureed and fed with a syringe in the 3rd week but the chicks will now also accept mashed fruits. For better digestion, I prefer introducing mashed fruits only in the 4th week while slowly also introducing small pieces of fruit. At this stage, the chicks can be fed with a pair of forceps or by hand.

½ a drop of vitamin drops and calcium drops must be added to three feeds daily. Probiotics too may be added if required – a pinch of probiotics thrice a day should suffice each chick.

Feeding quantity and frequency: The chicks may only be fed every hour in the 3rd week and every hour and a half in the 4th week as they will now be able to consume larger quantities in one go. Feeding must begin by 7 am and continued till about 7 pm.

Special care: External heat may be discontinued during the day [unless the days are chilly] in the 3rd week but will still be required at night. The ambient temperature may be maintained at 100˚F for the chicks at this stage. Thermoregulation develops by this age and as the chicks are now also feathered, they retain heat a lot better. External heat may be totally discontinued in the 4th week but the chicks must nevertheless be housed in warm spaces at night.

Chicks get competitive and aggressive at this age. They often peck each other in competition and typically aim for the face and eyes of the other chicks. In most cases, this is normal competition between the chicks; but you may consider separating them if they seem too aggressive and likely to physically hurt the other chicks. Once the chicks are a little older, they will themselves move out of harm’s way and although the competition will continue, there will be little risk of physical harm.

Stage 3: Fledgling – dependent upon parents

Characteristics: The chicks fledge by the time they are 4-5 weeks of age. Flying feathers develop with speed at this age; yet, their bodies will not be covered in adequate insulating feathers. A thicker layer of insulating feathers only starts to develop only once the chicks have left the nest.

Feed: The chicks will now readily accept small cut pieces of fruit: banana, chiku, muskmelon (the orangy ones), figs, etc. The chicks are naturally attracted to orange, red, yellow and brown coloured fruits and will soon even ignore bananas. Mashed egg must be continued if the chicks readily accept it; in most cases, they don’t.

Feeding quantity and frequency: A plate of chopped fruit must be given to the chicks 5-6 times a day. The plate must be left before them to encourage eating on their own and fruit must be replaced every 2 hours. The chicks start feeding by themselves at this age and will be completely off hand-feeding within 4-5 days of fledging. Intermittent hand-feeding must be continued for a week or two after fledging until they chicks are consuming an adequate quantity themselves. To encourage eating on their own, offer a plate of chopped food and draw the chick’s attention to it. To encourage independence, the plate must be offered to the chicks when they beg instead of offering pieces of fruit by hand – they learn to pick up pieces of fruit faster this way.

By the time the young birds are 6 weeks old, i.e. a couple of weeks after fledging, feeding may be reduced to 4 times a day. A plate of chopped fresh fruits may be offered to the birds early in the morning, mid-morning, early afternoon and late afternoon. Older birds rarely eat after 5-6 pm – they prepare to return to their roosts at this time.

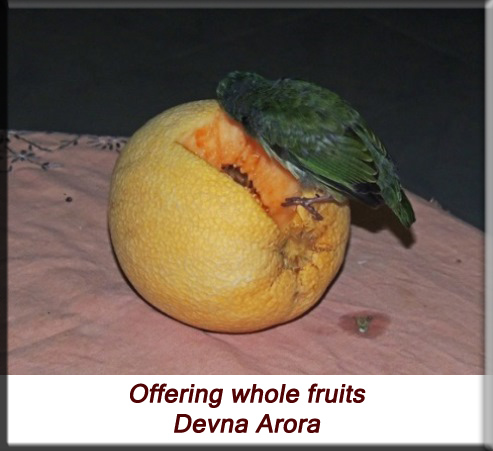

The young birds will eat on their own and hand-feeding must have ceased completely by six weeks of age. In nature, barbets typically swallow whole fruits and berries, and the fruits must now be given in big pieces – just big enough for them to swallow. The chicks will also not require skinned fruit anymore. In fact, they must be encouraged to have whole (i.e., with the skin) fruit pieces.

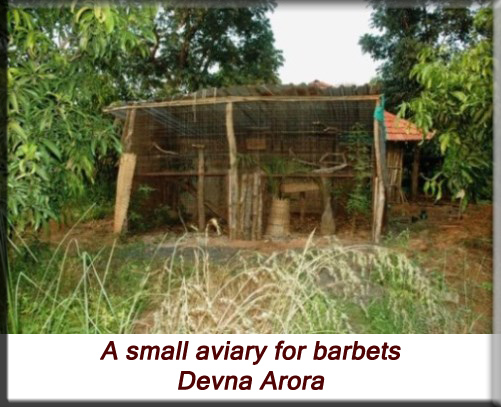

Special care: The chicks must be shifted to an aviary at this stage as they need flight practice before release. The aviaries must also have a nest box for the chicks as they would prefer to roost in the box at night. Alternatively, they may be shifted indoors for the night.

The chicks don’t require any external heat at this stage but must nonetheless be given warm roosting spaces at night, at least until a week or two after fledgling. What they essentially need is something to block off the cool breeze at night until they are a little older. Insulating feathers also rapidly develop at this stage and by 6 weeks of age, the chicks will be well covered in insulating feathers. They may now be allowed to sleep in their aviaries and may even prefer to just sleep on branches instead of going into nest boxes.

Once the chicks start to eat by themselves, they will attempt to pick up anything brightly coloured that stands out against the background. Often, they will pick up and ingest their droppings for the first few days until they are able to distinguish between their dropping and actual food. Droppings must be picked up frequently to prevent this. A bowl of fresh water must also now be available for the chicks at all times as they will now start drinking water. It is also a good idea to offer a big and shallow bowl of water for the birds to bathe in – they will certainly enjoy it during the summer months.

Stage 4: Fledgling – independent

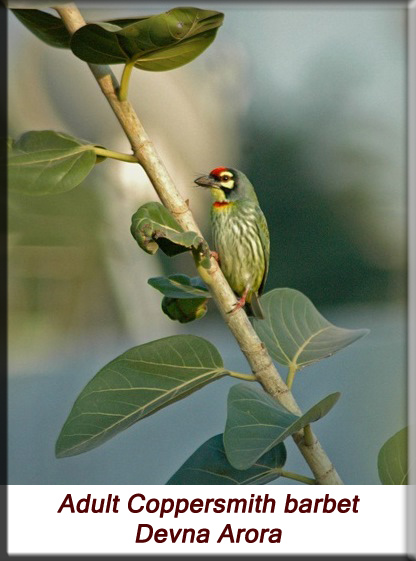

Characteristics: The secondary plumage feathers begin to erupt by 8-9 weeks of age and the chicks have the characteristic adult colours by the time they are 10-11 weeks old. They are still fledglings at this age – notice in the pic above how they hold the wings just as fledglings do.

Feeding: The chicks will now consume an adult diet and will begin to consume a wide variety of foods. Although the primary diet will consist of figs, they will now readily consume banana, chiku, grapes, pomegranates, papaya, boiled peas, musk melon, water melon, guava, plum, java plum (jamun), carissa congesta (karvand), etc. Boiled eggs and caterpillars must still be offered every once in a while. Wild picked berries and fruit must now be introduced to their diet – this helps them familiarize with the foods available in the wild.

The birds must be offered a combination of whole fruit and some chopped fruit pieces. The whole fruit encourages the birds to learn to peck small pieces out of whole fruit as they will consume many fruits that cannot be swallowed whole. Fresh food and water must be available for them at all times.

Special care: The chicks are now completely independent and must be readied for release. The process of soft release begins at 12-15 weeks of age, whereas birds being released though a hard release must be left after they cross 4 months of age.

Stage 5: Sub-adult/Immature

The chicks will appear brightly coloured and very muscular at this stage. They will have achieved 70% of their body growth and the beak may still appear proportionally a little larger.

They are now completely independent and must have been released by this stage. If opting for a hard release, this is the right time to release them.

Stage 6: Adult birds

Adult barbets will be completely independent and should have completely stopped returning to the aviary. They will breed in the following season.

Rehabilitation and Release

The young birds must be must be shifted to an aviary at the time of fledging and given adequate flight exercise before release. This is essential for them to develop the agility and swiftness required for survival. The aviary must be at least partially sheltered so the birds are not exposed to harsh sunlight throughout the day. Food at this stage must not be offered in one place but scattered around throughout the day so the young birds learn to search for it. Care must be taken to prevent the chicks from flying into the mesh and injuring themselves. Fresh drinking water and a larger shallow bowl of water to bathe in must be available at all times. The aviary must also have a couple of nest boxes, hung higher in the aviary, for the young birds to roost in.

The first step towards getting your bird ready for release is to break the young bird’s dependency on human beings and to give it maximum opportunities to be tuned in to its natural instincts. The process of rehabilitation must actively start by the time the chick fledges and followed meticulously until release.

Important things to be kept in mind when releasing barbets

1. Place of release and the prevailing environmental conditions

Wherever possible, all rescued animals must be released where they have been picked up from. This is particularly important when releasing animals that had been admitted to care centres as adults so they can have the chance to go back to familiar and known spaces. Younger birds must be released in suitable locations with good tree cover and ample fruiting trees, particularly figs, and in locations where they will be easy to monitor for the first few days after release.

The only instance where release to the same location must be avoided is if there have been irreversible changes which led to the initial displacement of the birds in the first place and will have rendered the place unsuitable for the survival of the species.

2. Age and timing of release

Birds that have been admitted as sub-adults or adults may be released just as soon as they are ready to be released. The only consideration for them is fitness for survival.

Birds that have hand-raised, on the other hand, need to go through a more protective method of release. Young birds may be released at the age of about 2½ - 3 months when opting for a soft release whereas those that are being hard released must only be released after 4 months of age.

3. Method of release

Birds may be released by following protocols for either a soft release, which is most ideal and recommended for hand-raised young, or through a hard release.

Hard Release is a means by which the animal is released into a new location without its being accustomed to the new environment. This process is appropriate for barbets that have been taken into care as adults.

Soft Release is a means by which the animal is gradually introduced or familiarized to a new environment before its release into that location. Hand-raised animals are at a disadvantage of not having had adequate parental learning and require additional safety and protection during release; hence the ideal way to release them is through a process of soft release.

The simplest way to soft release a barbet is by allowing it to fly in-and-out of its enclosure for the first few weeks after it fledges and becomes fairly independent. The young must be shifted to enclosures where they will be released from so that they can identify the enclosure and their surroundings – this will help in building site fidelity and make it easier for them to return to the safety of the enclosure until they are completely independent and ready to leave. The young birds may be allowed to fly out in a few weeks thereafter through a couple of openings/windows in their enclosures. At this age, the birds will not fly far and return to their enclosure several times during the day and most certainly to roost at night. The access opening and windows must only be opened at dawn and closed at night to prevent entry of predators like rats, cats, snakes, etc.

Once they have explored their surroundings and have found safe roosting spaces for themselves (typically in a few weeks), they will cease to return to the protection of their aviary but may return for titbits of food. Eventually, they will become completely independent and cease to return to the aviary at all. Supplemental feeding must be continued until the birds are independent but may be ceased once the birds are self-sufficient.

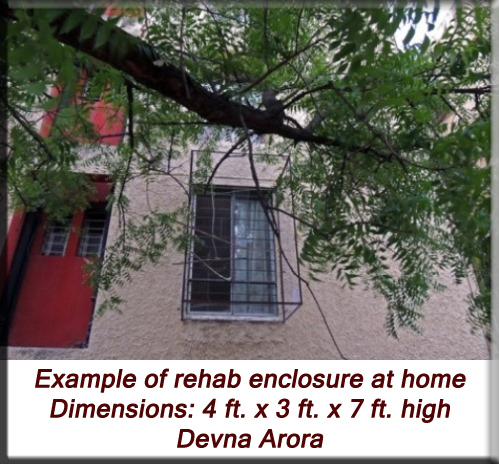

Birds may be released in a similar manner if hand-raising and rehabbing from home [appropriate only for species that are found near your home – this mostly applies only to Coppersmith barbets]. Consider a small cagey extension out of any room or window – this system works best in apartment buildings. The extension may simply be a light frame with wire mesh if there is no threat of cats – this is inexpensive and very easy to install. I used the method below and periodically let the young birds in the room to exercise their wings.

Although barbets are generally very independent, birds being rehabilitated and released from homes may return for longer durations as they are likely to have stronger bonds with both the homes and the caregivers. They may also visit every now and then well after the gain complete independence. Do refrain from encouraging the birds to enter the house if the birds visit you. Birds that are accustomed to entering the house are twice as likely to accidentally fly into someone else’s house and land into trouble.

Note of caution: A ceiling fan must never be used in a room with birds to ensure they don’t fly into a moving fan and get injured fatally.

References and further reading

Avianweb LLC (no date) Coppersmith barbets or crimson breasted barbets [Online]. Available from: http://www.avianweb.com/coppersmithbarbets.html[Accessed: 22/03/2013]

Blanford, W.T. (1895) The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma: Birds – Vol. III, Taylor and Francis, London, pp. 82–100

Damian Shaheen (no date) Bearded barbets – growth [Online]. Available from: http://www.cajunbait2000.net/barbets.html [Accessed: 23/03/2013]

Frank Indiviglio (2012) Barbets - Stunning, Unique Aviary Birds for Experienced Keepers [Online]. Available from: http://blogs.thatpetplace.com/thatbirdblog/2012/03/21/barbets-stunning-unique-aviary-birds-for-experienced-keepers/[Accessed: 22/03/2013]

Khong Tuck Khoon (2009) Nesting series – Coppersmith barbet [Online]. Available from: http://www.malaysianbirds.com/nesting/barbet.htm[Accessed: 22/03/2013]

Khong Tuck Khoon (2009) Nesting series – Coppersmith barbet – pg 2 [Online]. Available from: http://www.malaysianbirds.com/nesting/barbet2.htm[Accessed: 22/03/2013]

Lok, A.F.S.L., Tey, B.S. and Subaraj, R. (2009) Barbets of Singapore Part 1: Megalaima lineata hodgsoni Bonaparte, The Lineated barbet, Singapore’s only exotic species [Online]. Available from: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/nis/bulletin2009/2009nis39-45.pdf [Accessed: 23/03/2013]

Lok, A.F.S.L., Yao, C.J. and Tey, B.S. (2009) Barbets of Singapore Part 2: Megalaima haemacephala indica Latham (Coppersmith barbet), Singapore's only native, urban barbet [Online]. Available from: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/nis/bulletin2009/2009nis47-54.pdf [Accessed: 22/03/2013]

Lok, A.F.S.L., Yao, C.J. and Tey, B.S. (2009) Barbets of Singapore Part 3: Forest species, with emphasis on Megalaima rafflesii lesson, The red-crowned barbet [Online]. Available from: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/nis/bulletin2009/2009nis69-76.pdf [Accessed: 23/03/2013]

Nashville Zoo (no date) Megalaimidae (Asian Barbets) [Online]. Available from: http://www.nashvillezoo.org/piciformes/megalaimidae.htm[Accessed: 23/03/2013]

National Council for Aviculture (2009) Barbets – “The ugly ducklings of the bird world” [Online]. Available from: http://server1.web-mania.com/users/betofbre/nca/factsheets/Fact_Sheet_26.pdf[Accessed: 22/03/2013]

Please note: This document is targeted at hand-rearing alone and does not address or substitute any veterinary procedures. For any medical concerns, please consult your veterinarian at the earliest.

For amateurs or people handling new born chicks for the very first time, please keep in touch with a trained and experienced hand for guidance and regular progress updates.

Protocol published in 2013

%20with%20a%20piece%20of%20fruit.JPG)