Protocols for the hand-raising and rehabilitation of mynas (contd.)

Corina Gardner

Link to Page 1: Protocols for the hand-raising and rehabilitation of mynas

Stage wise care and feeding instructions for the chicks

0–2 week old chicks

New born mynas are born totally pink, featherless, blind and completely helpless. Pin feathers begin to erupt in the second week of the baby’s life and the babies’ eyes usually open around the 8th – 10th day. Fresh hatchlings require extensive care and need to be fed almost round-the-clock. It would be unnecessary to feed the baby at night as in nature, parent birds as well as the babies sleep at night.

Ideally, feeding should start at 6 a.m. and continue until midnight. The chicks should be given 10 feeds a day at intervals of 2 hours. A day old chick would require approximately 1 ml of formula per feed, which can be gradually increased to 2 ml by the 4th day and 3 ml by 7th day. The feedings can also be reduced to 8 feeds by the end of the 10th day. Two feeds – one around mid-morning and one around mid-afternoon, may be replaced by mashed/pureed soft fruits like banana, mango or papaya instead of the formula.

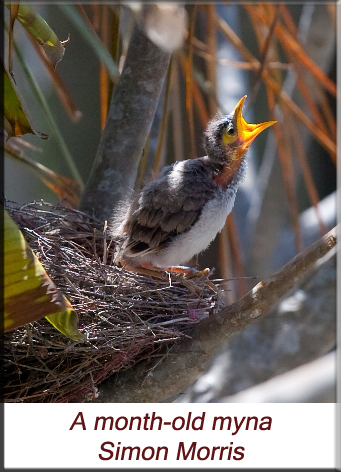

2 – 4 week old chicks

Even though the nestlings are covered with feathers, there is still a while before the flight feathers develop. The baby can now be given about 7 feeds a day. Gradually reduce the feeds to six times a day. Feeding however must still begin by 6 a.m. and the last feed could be given by 10 p.m.

The baby can now be fed on a combination of sattu and fruits as well as mashed hard-boiled egg. Mashed/pureed banana, papaya, mango, sapodilla (chiku), mixed with crumbled up biscuits (marie or cream cracker would be ideal) are good options to add to their diet. If possible, insects such as grasshoppers, caterpillars and crickets could also be fed to the babies.

You can either offer them a mix of sattu and fruit, or the feeds may be alternated with sattu in one feed and fruit in the other. Avoid repeating any one fruit over and over again; instead, it would be better to offer them different fruits at intervals. This would be easier for them to digest and also ensure an intake of varied nutrients from different fruits.

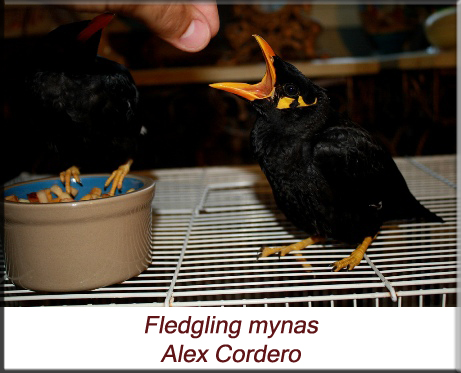

4th – 5th week

The fledgling now starts to develop flight feathers by this age and will soon fledge in a couple of weeks. The young mynas can now be given 4-5 feeds a day, about 5 hours apart. They also start foraging (searching for food) themselves by this age. The weaning process must begin by the time the chicks are 5 weeks old. Make sure that there is always food available for them so that they can start eating on their own and gradually become independent although you should still carry on hand-feeding the feedings.

6th – 7th week

The young bird is quite independent and starts to search for food. Put small morsels of food in his cage and he will start to eat on his own. Now is also the time to transfer the bird to an outdoor enclosure. Although they feed well by themselves at this age, they must be watched vigilantly to ensure they are eating well. If necessary, hand feeding can be continued once or twice a day. A bowl of fresh water must be available at all times for the young birds as they will now begin to drink water. The young birds may now be offered fruit chopped into small pieces, sattu pellets, pieces of hard-boiled egg as well as boiled rice and dal (lentils).

8th – 9th week

By 8 weeks of age, the young bird should be completely weaned.

Offer the fledgling a varied diet by this age. Allow them to explore and make choices for themselves. Their diet can now include a variety of fruits, berries and insects, such as grasshoppers and crickets.

Adult bird diet

Mynas are soft bill birds and primarily only eat soft foods. They do not eat seeds. In captivity, their diet consists of sattu pellets, cooked rice and dal, hard-boiled egg, insects and fruit. Green leafy vegetables such as lettuce, mustard sprouts, millet sprouts and fenugreek (methi) leaves are also very essential.

Mynas drink plenty of water and their water bowl should always be clean and filled with fresh water. The water should be changed frequently. Mynas also enjoy frequent bathing, so it is necessary to keep a shallow bowl filled with fresh water for the birds to bathe in.

Foods to be avoided

Foods that are highly toxic for birds include apple pips, avocado (makhanphal), cherries and peaches (aadu) and must never be given to the birds. Never give the birds chocolate, as it may make the bird seriously ill.

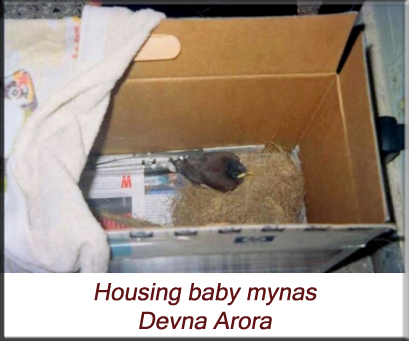

Housing the young birds

A shoe-box or a small cardboard box with adequate holes for ventilation, a wicker basket or even a small aquarium may be used to house the young birds. The box can be lined with a soft towel at the base and a few layers of paper towels and strips of paper on top of the towel, as paper towels are easier to change when dirty.

The box must be placed in a warm, dry place, preferably near an artificial source of warmth. A heating lamp, with a light bulb of maximum 40 watts, can be placed above the box to provide warmth to the chicks. The lamp must be placed at least 12” away from the box. The ideal temperature for the baby birds would be about 35.5° Celsius (or 96° Fahrenheit). Again, it is crucial to be vigilant and ensure that the baby is not being overheated. A clear indication of overheating would be when the baby’s beak is open (as if panting) and wings are held away from its body. Unlike mammals, birds lack sweat glands and hence cannot sweat. To release excesses body heat and afford a cooling effect, they open their beak wide and pant, causing moisture to evaporate from the oral cavity and in turn cooling the body. On the other hand, if the bird is huddled and shivering, it is not receiving enough warmth.

The box must be partly covered with a light towel at night to keep out the light from the heating lamp and thus enabling the baby to sleep. It must be noted that the purpose of the lamp is to provide warmth alone and not light and it must never interfere with the natural light patterns and disrupt the baby bird’s sleep cycle. Even when in captivity, the parent bird sits on the baby, shielding it from most of the light. The heating lamp may be discontinued after the baby crosses 2-3 weeks of age and is covered with its first layer of feathers.

Ants are a real danger to baby birds and can fatally hurt them. It must be ensured that there are no ants in the vicinity of the bird.

Sexing mynas

Mynas are sexually monomorphic species and sexing mynas on appearance or behavior alone is extremely difficult. Mynas very seldom reproduce in captivity which further adds to the confusion. However, they are a few indications to ascertain the difference between male and female mynas. Within the same species, male mynas are larger than the females. The wattles of male mynas appear larger. Hill myna males have distinctly flatter heads than females, whereas the female mynas have a more rounded head. Another indication that the myna is male is the fact the pelvic bone in the male myna is set closer than in the females.

Preening

Mynas frequently preen their feathers. Birds use their beaks to preen their feathers and keep them in good condition. Preening is an essential way for birds to keep their feathers neat and trim.

Rehabilitating the young mynas

By the age of 3 months, the young mynas should be shifted to an aviary, preferably one with some fruiting trees. They must be provided with a nest box to retire in at night and during harsh weather. Human contact must be withdrawn from the birds and they must be encouraged to be independent.

Avoid placing a feeding table in the enclosure. Instead, place the food in different sections of the enclosure every day. The placement of foods must be rotated so as to encourage ‘searching’ behavior in the young birds. Food must also be placed at different height levels so as to get the birds used to foraging at various levels of height. The birds must be offered a variety of foods to prevent dependency on any one food type. A significant proportion of their diet must now comprise of wild-gathered foods as it will assist their transition to the wild and help them recognize readily available foods. The birds must have access to fresh drinking water at all times and they must frequently be given provisions to have a bath.

Soft release

By the age of four to five months, the young mynas will be ready to explore the outside world. Common mynas and Jungle mynas are highly adaptable species which makes it easier to release them in any convenient surroundings where they will be able to find sufficient forage. Hill mynas on the other hand are habitat specialists and need forested landscapes for survival. The young birds must now be shifted to an aviary. The aviary for Common and Jungle mynas may be in any suitable location whereas the aviary for Jungle mynas must be in a forested landscape.

By four to five months of age, the mynas may be allowed to exit the enclosure via a window (an opening) in the aviary. The window may either be on the side or the top of the aviary. The window must be opened early in the morning and closed by sunset. The birds will initially fly around and come back to the enclosure for a few weeks. As they grow older and have explored their surroundings thoroughly, they will begin to stay away for longer durations of time, until they have established a territory of their own and no longer feel the need to return to the enclosure. They should be completely independent by 6 months of age.

Hard release

Although a soft release is ideal for hand-raised birds, there may be instances where you may have to opt for a hard release for the young mynas. The minimum age at which the bird may be released is 6 months of age. Habitat selectivity may carry more importance when opting for a hard release. Hill mynas must only be released in forested landscapes while Common and Jungle mynas may be released in any suitable habitats.

Sickness in mynas

Egg binding

Egg binding is a medical condition when a female bird is unable to expel an egg. Egg binding can pose a serious threat to female birds. Younger females are at a greater risk of dying from egg binding. In the event that a female myna is suddenly puffed-up and listless, it is quite likely due to egg-binding.

The female must immediately be placed in a small cage or shoe-box and provided with quiet and additional warmth. A heating lamp would be ideal. Castor oil or even cooking oil can be gently applied in to the birds vent or cloaca, with a Q-tip (a cotton bud) to lubricate the area and facilitate the passing of the difficult egg. One drop of castor oil given orally will also help the passage of the egg. If these basic requirements are provided it is unlikely that the bird will suffer any serious health issues.

Abnormal droppings

Green droppings usually indicate an infection. Birds fed on soft food and greens may normally produce green and watery droppings, but if the droppings are runny and bubbly as well as carry an odor and persist over a period of time (especially if the bird is fluffed up, lethargic and has a loss of appetite), it indicates a chill or an infection. A pinch of Ridol, Kaltin, terramycin or any other antibiotic tablet can be dissolved in a half container of water. The infection should likely subside in a day or two and the medication may be discontinued a day after the bird has returned to normal health. Avoid exposing the birds to a cold breeze or draught, especially at night, as this causes chills and other health problems. Avoid offering fruits at this time; cooked rice and boiled egg are a good option instead.

Fungal infection

Aspergillosis is the most frequently occurring fungal infection in birds. It is primarily a disease of the lower respiratory tract. There is a high prevalence of infection in mynas.The spores of the fungus are often present in the environment and healthy, unstressed birds are generally resistant to even high levels of spores. Birds with a weakened immune system, or high stress levels (due to environmental changes), are most susceptible to the disease. It may be contracted as the result of inhalation of fungal spores, fecal material or soil, or oral ingestion, especially if the birds are fed moldy food or housed in a contaminated environment.

It is therefore extremely important that feed is properly stored and is free of fungal growth. Proper ventilation in the enclosures is also essential. Most importantly, the birds must be fed a healthy diet.

Symptoms of a fungal infection include constant sneezing, coughing or labored breathing, loss of appetite and diarrhea. It can be life threatening if left undiagnosed or untreated.

Treatment: The infected bird must be immediately isolated from other birds and provided with a quiet environment and additional warmth – a heating lamp would be ideal for this purpose. Antifungal tablets like Amphotericin B, Flucytosine, Fluconazole or Itraconazole must be added to the bird’s drinking water. You could also consider using Teeburb tablets which is an herbal veterinary preparation. Immunostimulants may also be added to the bird’s diet to facilitate recovery. However, if you find that the bird is not drinking the water, then the medication will have to be force fed.

References and further reading

Bockheim, G. and Congdon, S. (2001) The Sturnidae husbandry manual and resource guide

Available from:

http://www.australasianzookeeping.org/Husbandry%20Manuals/

sturnids.pdf [Accessed: 26/08/2012]

Gardner, C. et al (2012) Protocols for the rehabilitation of baby Ring-necked parakeets (Psittacula krameri), Rehabber’s Den

Available from:

http://rehabbersden.org/Rehabilitation%20of%20baby%20Ringneck

%20parakeets.pdf [Accessed: 25/06/2012]

Houston, J.P. (2009) Hand-rearing softbills, The Foreign Softbill Society UK

Available from:

http://fssuk.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=28:hand-rearing-of-softbills&catid=14:husbandry-articles&Itemid=29 [Accessed: 26/08/2012]

Indiviglio, F. (2008) The Natural History and Captive Care of the Hill Myna (Myna Bird, Indian Hill Myna), Gracula religiosa – Part 1, That Bird Blog

Available from:

http://blogs.thatpetplace.com/thatbirdblog/2008/05/08/the-natural-history-and-captive-care-of-the-hill-myna-myna-bird-indian-hill-myna-gracula-religiosa-part-1/[Accessed: 26/08/2012]

Indiviglio, F. (2008) The Natural History and Captive Care of the Hill Myna (Myna Bird, Indian Hill Myna), Gracula religiosa – Part 2, That Bird Blog

Available from:

http://blogs.thatpetplace.com/thatbirdblog/2008/05/10/the-natural-history-and-captive-care-of-the-hill-myna-myna-bird-indian-hill-myna-gracula-religiosa-part-2/[Accessed: 26/08/2012]

Stewart, K. (2002) Hand-rearing guide for the beginner, Lori~Link

Available from: http://www.kcbbs.gen.nz/lori/ar/handrear2.html[Accessed: 26/08/2012]

Walker, C (undated) Megabacteria infection in birds

Available from:

http://www.anbc.iinet.net.au/downloads/megabacteria_update.pdf[Accessed: 28/08/2012]

Wikipedia (2012) – Myna

Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myna[Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Photographs used

Alex Cordero – 3 week old myna chicks

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/httpthesoftbillgallery/7562579818/in/

photostream/ [Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Alex Cordero – Fledgling mynas

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/httpthesoftbillgallery/6773177857/[Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Alex Cordero – Gapers

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/httpthesoftbillgallery/6939845264/[Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Caroline Dreams – Two week old myna

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/liltree/24217766/sizes/z/in/photostream/[Accessed: 17/08/2012]

David Lim – Hill mynas

Devna Arora – Brahminy starling

Devna Arora – Jungle myna

Devna Arora – Housing baby mynas

Devna Arora – Pre-release aviary

Dr. Lip Kee Yan – Bank mynas

Available from: http://www.flickr.com/photos/lipkee/3196315385/

[Accessed: 23/08/2012]

Nupur Buragohan – 10 day old baby mynas

Nupur Buragohan – Placing a basket as an artificial nest for baby mynas

Om Prakash Yadav – Adult male hill myna

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/opyadav/6105609819/[Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Tris – Common myna

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/trissysviewpoint/6385394335/[Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Rosa Say – Myna chick fallen from the nest

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosasay/2629762970/[Accessed: 24/07/2012]

Simon Morris – A month-old myna

Stephen Witherden – mynas nest

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/swit012/4734358109/sizes/l/in/

photostream/ [Accessed: 19/07/2012]

Acknowledgements

I’d like to add a special thank you to Dr. Nupur Ranjan Buragohan for his invaluable guidance and suggestions on the drugs for the treatments of the birds.

Edited by Devna Arora

Published in 2012