The House Sparrow Passer domesticus: Nesting, Orphan Care and Rehabilitation

Gover Mistry, Devna Arora and Palak Thakor

The House Sparrow

The house sparrow (Passer domesticus) is a small passerine bird widely distributed across old world countries in the northern hemisphere and is now also commonly found in several other countries, both in the northern and southern hemisphere, beyond its native range. The species is commonly found in rural and suburban landscapes and lives in close proximity to and dependency upon humans. However, the species has been on a steady decline throughout its native range and populations have reduced to half or less in many of its native ranges.

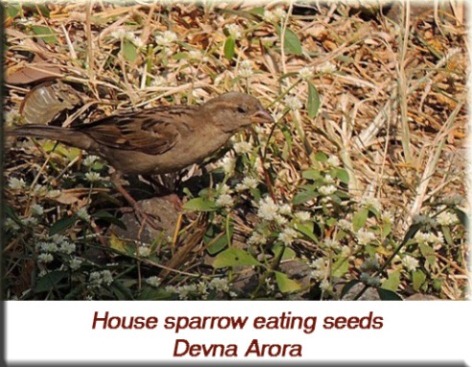

House sparrows are primarily granivorous birds and forage on the ground for fallen grains and seeds of grasses but will also readily consume cooked grains, biscuit crumbs, cultivated seeds, crushed nuts and animal protein including caterpillars, butterflies, moths and other small insects.

Nesting behaviour

House sparrows are highly gregarious birds and it is not uncommon to see hosts of them flocking together. Pairs fiercely defend their nests but don’t mind other sparrows nesting a foot-or-so away from them as long as there are sufficient nesting spaces. Sparrows typically mate for life and both parents are actively involved in rearing the chicks. They also show high nest fidelity and return to the same nests every year to breed. The life expectancy of house sparrows is 6-10 years on average while individual birds have been known to live longer.

The species mostly breeds between the summer months of February and June in tropical countries and April to August in temperate zones, and has been known to have raised 2-3 broods of chicks in good seasons. Nests are made in small cavities like eaves of houses, holes in brick walls, dense trees and bushes and other natural and man-made cavities.

Although sparrows have been known to lay 4-5 eggs per clutch, recent observations have indicated a steady decline in the numbers of eggs per clutch in many places. Comparisons of broken egg shells also indicate noticeable thinning of the shells over the years (personal observations over two decades). Even though people have been making a conscious effort to encourage breeding by placing artificial nest boxes for sparrows, only 1-2 chicks have fledged in cities like Pune (Maharashtra, India) in recent years.

Records from temperate zones record an incubation period of 10-14 days and eggs are actively incubated by both parents. Chicks are actively fed by both parents and they fledge at the age of about 15-18 days. In contract, observations in more tropical zones indicate an incubation period of 20-21 days and the chicks fledge at the age of about 20-25 days. It is the female that actively incubates the eggs while the male guards the nest and feeds the female while she sits on the eggs. Although the male provides the female with nearly half her daily requirements during incubation, she makes brief visits to feed, drink or defecate away from the nest. Meanwhile, the male moves closer to the nest and guards the nest until the female returns. Once the eggs hatch, both parents actively take turns in feeding the chicks.

Female sparrows noticeably lose weight during the nesting period. It is also interesting to note that the beak of female sparrows with chicks is visibly lighter than those of other female sparrows and females with active nests can therefore be easily identified.

N.B. There is a noticeable difference in the age of fledging of sparrow chicks in different latitudes. Sparrows in temperate zones, due to longer daylight hours of the summer months, feed their chicks from about 4–5 am to about 11 pm each day. This helps the chicks to develop and fledge at a faster rate than those in more tropical zones. Those living next to artificial light sources may enjoy similar benefits. Whereas sparrows living in tropical zones only begin feeding their chicks at about 6 am and will cease feeding for the day by approximately 7–8 pm.

Sparrow chicks are dependent on their parents for at least a week or two after they fledge and are continued to be fed by the parents until they start feeding themselves. It is now the male that primarily keeps an eye on the fledglings and accompanies them everywhere. The female, in the meanwhile, replenishes the lost energy and prepares for the second brood of chicks.

Need for assistance

In the event of the demise of one parent, sparrow chicks are less likely to be found in helpless situations as the other parent continues to care for them. The chicks therefore are most commonly found during the fledgling stage when they either jump out of the nest too soon or are unable to keep up and land in unsafe locations. If the parents and the nest can be identified, such chicks must be placed back in their nests at the earliest. The chicks must not be returned to just any sparrow nest if unsure of the parents and nest of origin as non-biological parents are unlikely to care for them or feed them. Attempts to reunite the chick may be made in subsequent days if the chick appears to be able to keep up and if the parents still appear to be protective of him/her. In all other instances, the chicks must be hand-reared and released at an appropriate time.

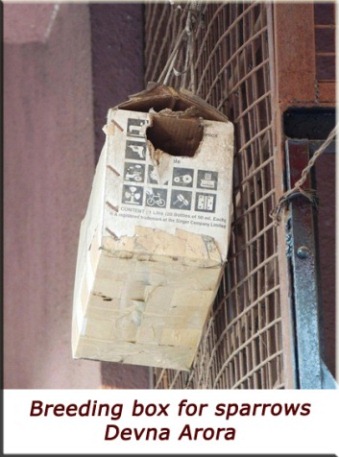

Finding fallen nests too is not uncommon, but rare. The simplest thing to do when you find a fallen nest is to place the chicks in an artificial nest and place it as close to the location of the original nest. Sparrows readily nest in shoe-boxes or similar sized boxes with a small hole to the upper end of any of its sides. The nesting material of the original nest may be placed inside the artificial nest and then placed at an appropriate location. Disturbance around the new nest must be avoided in all instances so as not to scare the parents away.

In most cases, the parents resume feeding the chicks in a couple of hours but if they don’t accept the new nest and resume feeding, the chicks must be brought indoors to ensure adequate warmth for the night and may be fed while they are still indoors. A second attempt at reuniting the chicks must be made at first light. The artificial nest box must be placed back before dawn to allow an uninterrupted visit by the parents. Chicks/Nests that have not been accepted by the parents by noon must be shifted into human care for hand-rearing.

House sparrow readily nest in close proximity to humans as long as they feel safe and will tolerate familiar human movement within a few feet of their nests.

Sexing House sparrows

Sexing mature sparrows is rather simple. The female house sparrow is light buff-brown in colour with no markings on her light coloured chest. The male, on the other hand, is brightly coloured with an ashy crown extending to its forehead and a black bib running down its throat.

General guidelines for hand-rearing sparrows

Hygiene

The chicks must be kept in extremely hygienic conditions until they are ready to fledge as young chicks are susceptible infections. Their bedding must be kept clean and changed as often as required. Hands must be washed every single time before touching the nestlings. Excessive handling of the chicks must be avoided and they must only be handled during feeding times, although in most cases, it will be absolutely unnecessary to touch the chicks when feeding them.

Housing

New-born chicks must be housed indoors in small nesting boxes. The chicks may be placed in small nesting cups and then placed in boxes. A nesting cup is simply a rounded bowl, 6-10 cms in diameter, with some soft cloth towels and paper towels on it.

The chicks must never be placed on the cloth towels directly as their nails tend to get caught in the fibrous loops of the towels. Cotton too must never be used to line the nests as it gets entangled around the chick’s beak and claws and also sticks to the droppings. The chicks must instead be placed on paper towels on the cloth towel which also makes it easier to clean and replace soiled bedding.

The nesting cup must be placed in a box, as this keeps warm air contained in the box, and placed under a heating lamp with the lid open. The distance of the heating lamp from the box will depend upon the wattage of the bulb. The chicks will require more warmth while they are unfeathered while the intensity of heat required will gradually reduce as the chicks become adequately feathered. The box must be covered with a cloth at night to prevent the light of the lamp from falling directly on the chicks and interrupting the natural circadian rhythm of the chicks.

Chicks will defecate several times through the day. Their droppings are enclosed in a capsule-like structure which makes it very easy for the parent birds to pick and drop them away from the nest. In most cases, you should be able to do the same and the paper towel lining may only be replaced a couple of times a day. But if you are unable to pick the droppings, then the towel must be replaced each time the chick defecates to prevent the droppings from sticking to the chick’s feathers and skin. Droppings harden after sticking to the body and are extremely painful to remove and inevitably peel off with a bit of skin, exposing raw skin to bacterial infections.

Feathered chicks/nestlings may be shifted to small cages. They must still be housed indoors but may be exposed to mild sunlight for a couple of hours every day. They may or not require additional warmth during the day which will be dependent on the prevailing weather conditions at your place, but will most likely still require mild heating at night.

On fledging, the chicks must be shifted to an aviary for adequate flight exercise before release. An aviary that is roughly 10 ft. X 10 ft. and 10 feet high is adequate for sparrow chicks. The aviary must be equipped with several perches but must allow the sparrows to fly about freely and exercise their fight muscles.

Inter-species interactions

The chicks must never be house in close proximity to predatory species like crows, hawks, cats or dogs. Housing the chicks in close proximity to such species will either lead to constant stress due to the smells, sounds and movements of the predators; or it will lead to habituation and lack of fear and decrease their chances of survival after release.

Imprinting

Imprinting is a process whereby a young animal learns and imitates the behaviour traits of its parents. It serves as an indirect method of instilling the appropriate behaviour and survival traits in young animals. Under the unnatural conditions of captivity, the chicks do not imprint on sparrows as they have never been exposed to any but on other humans and animals they are exposed to.

I am embarrassed to admit that I (Devna Arora – personal experiences) have, in the past, had a sparrow chick that had imprinted on palm-squirrels as they were housed in the same room. She would follow them everywhere, try and behave like them, squeeze into tiny spaces along with them, and attempt to eat the foods that the young squirrels were eating. Although she was independent by the time she fledged, she was turning out to be more of a squirrel dressed in a pair of wings. Fortunately, this behaviour was recognized and corrected immediately and the first step towards her rehabilitation was to break her contact with the squirrels and expose her to more birds and luckily for us, it worked and she adapted beautifully to normal sparrow behaviour. But, such behaviours must never be allowed to manifest in the first place.

The first rule of hand-raising an animal that is to be released is to prevent imprinting by the wrong species. The youngster must therefore never be housed with animals of other species. Handling of younger birds must be restricted to 1-2 caregivers. The chicks must only recognize the primary caregiver and not depend upon humans for care. This will prevent it from approaching humans for food and begging.

Warmth

Birds, especially smaller sized birds like house sparrows, have higher basal metabolic rates and higher body temperatures. The average body temperature of small passerines is between 39˚C – 43˚C (102˚F – 107˚F). The chicks therefore require additional warmth to maintain higher body temperatures in the initial few weeks of their lives and must always feel slightly warm on touch. As a rule of thumb, the smaller the chick, the more warmth it will require.

Most breeding centres and rescue centre nurseries are equipped with incubators and prefer the same for baby birds. It is easiest to both control and monitor the temperature of the nest chamber when using incubators. But these may not be easily available to individual rescuers, in which case, alternate methods of providing external heat are required.

A primary advantage of summer breeders is that they nest during the warmer months of the year and the chicks require little additional heat when kept at room temperatures. Although it is difficult to monitor the heat produced by heating lamps, they adequately serve the purpose of providing heat for nestlings. A room thermometer placed in the box will help you gauge the temperature and adjust the distance of lamp as and when required. Chicks that get too warm will pant to decrease their body temperature. If such behaviour is noticed, external heat must be reduced and ventilation increased immediately to prevent over-heating.

Hot-water bottles are also used to provide external heat for the chicks and are safe to use with smaller birds. The bottle, wrapped in a couple of layers of cloth, must be placed under the chick’s bedding and it must be ensured that the chicks cannot come in direct contact with the bottle as they will scald if they do. Hot-water bottles must only be placed under half of the chick’s bedding leaving them the flexibility to shift to the uncovered part of the box if they get too warm. They may therefore not be ideal for use with nesting cups but convenient instead for bigger housing boxes.

Water and hydration

Baby birds are seldom given water orally. They receive adequate water through their feeds. Birds have no means of carrying back water for their chicks nor can they lead their chicks to water and lead them back to their nests. It is in extreme cases when the temperatures rise very high that the parent birds may dip themselves in water so the chicks can lick the water off their feathers – however, this behaviour has not been documented in house sparrows.

Baby birds must be offered soft and moist foods both assist digestion and ensure sufficient hydration. Mild dehydration may be addressed by offering the chick softer foods or formulas until dehydration has been addressed. To help restore the electrolyte balance, rehydration electrolytes may be added to the water that is used to soak the chick’s food in. Refrain from administering water orally as the risk of water going down the trachea and aspirating the chick is high. If severe dehydration exists, the chick may be given fluids subcutaneously but this must only be done by an avian veterinarian. Such chicks must be fed only after dehydration has been addressed.

Baby birds that are dehydrated will appear weak and listless. Their skin, especially around the breast and stomach, will appear tighter and wrinkled. The skin turgor test or the ‘tent test’ may also be used to assess dehydration. Well hydrated chicks, on the other hand, are soft to touch and appear rounded and well. They will also be a lot more active and interested in movements around them than dehydrated chicks.

Feed

The chicks need to be fed every half hour until they fledge and will consume about 5% of body weight in each feed. Feeding must begin at dawn and continue for the next 15 hours or so until later in the night. If feeding several chicks, you must ensure that all chicks are well fed as the runts or weaker chicks often get pushed aside and may consequently get weaker if not given adequate attention.

Baby sparrows can be given a vast variety of foods which include cooked rice, boiled egg, moistened glucose or maire biscuits, bread dipped in little milk, cake or pancake crumbs, whole-wheat dough, sattu or roasted chickpea flour (besan) dough, dry cat food soaked in water, flaked rice (poha), rolled oats, broken wheat porridge, chapattis, peanut butter, crushed seeds, fresh sprouts, soaked grains like rice, millet (jowar, bajra), bird seed and cereal mixes. Different feed combinations will be appropriate for the chicks at different stages of their growth and development – details given in the nest page on ‘stage-wise care’.

Caterpillars are an excellent source of nutrition and, if feasible, must be added to the chick’s diet. They may be wild caught but the easiest way to obtain caterpillars is by combing through rotten vegetables like cauliflowers and peas. Caterpillars must nonetheless be picked carefully as some species can be poisonous and harmful for young birds. Grasshoppers and crickets may also be added to the chick’s diet.

Avian vitamins and calcium like Avitron, Avimix, Zolcal-D, etc., if available, are ideal supplements for baby birds. The next best choice to avian supplements would be other veterinary or paediatric combinations such as Zincovit, Sancal pet or A-Z drops. Most multivitamin combinations do not include calcium and this may be supplemented in addition to the brand available. We also recommended the addition of probiotics to the chick’s feed. Avian probiotics like PetAg’s Bene-Bac Plus or human preparations like Vibact or Bifilac may be used for the chicks. The exact doses may be obtained from an avian veterinarian.

Baby bird formula, like Kaytee’s Exact hand feeding formula or Hagen’s Tropican baby hand-feeding formula, available in most pet stores, may be used in combination with other foods for hand-rearing baby sparrows. However, as these are not easily available in many parts of India, other foods and infant cereals like Cerelac, Farex or Nestum (Stage I or Stage II – Rice, Wheat and Wheat-Apple) may also be used for baby birds.

Only boiled water must ever be used to prepare the feed. Refrain from preparing the feed in plastic containers as they are concerns over chemicals like BPA leaking into the formula if stored and heated in plastic containers. A fresh batch of feed must be prepared for every feed and all leftovers must be promptly discarded as using stale feed can lead to bacterial infections.

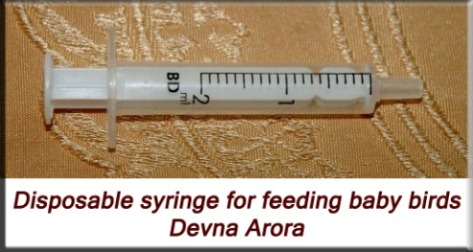

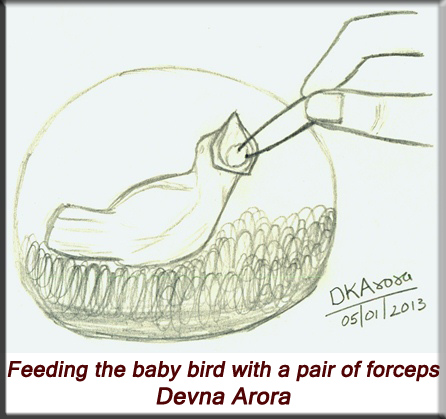

The formula must however be fed using a feeding syringe whereas the other foods can be fed to the chicks using a pair of blunt-tipped forceps or tweezers. The consistency of the formula should be similar to that of a soft pudding – neither too thick, which would make it difficult for the baby to swallow and it may choke, nor too diluted as the baby could inhale the formula into its lungs causing aspiration. The chicks must be fed warm formula just as mammalian young are given warm milk. Formula that is too hot will scald the baby bird’s crop, causing crop burn. Crop burn is the scalding of the chick’s crop and oesophagus. Cold formula, on the other hand, will slow the process of digestion and cause ‘sour crop’. Sour crop is a condition in which the formula in the chick’s crop has gone bad as the contents of the crop have not emptied.

Note of caution on the use of milk for feeding the chicks

Milk is in no way a natural part of any bird’s diet. Baby birds do not require milk for growth and do not readily digest milk. Providing an inappropriate diet will disturb the microbial balance of the gut flora and can result in severe diarrhoea. Infant cereals that contain milk have however been used successfully for hand-rearing several species of birds. Studies and experiences of aviculturists indicate that baby birds may tolerate up to 5% of milk in their diet without it causing them any harm. Nonetheless, wild sparrows have often been observed preferring bread and milk to feed their chicks over other available alternatives but this may simply be due to the palatability of the feed. Although we personally do not propagate the use of milk for baby birds, observations of wild sparrows indicate that milk may be used in minute quantities for baby birds.

Feeders

A pair of blunt-tipped forceps or tweezers is ideal for feeding baby sparrows. These are easy to use, comfortable for the chicks and easy to clean. They only need to be washed with soap and water after the feed.

Feeding syringes are required for feeding formulas as formulas are much too soft to be picked up with tweezers or forceps. Syringes however have to be sterilized after every use. The syringe must be rinsed to wash off any feed residue and then boiled in boiling water for 5 minutes to sterilize it. Not sterilizing the feeders will lead to a build-up of bacteria in the feeders which can prove to be fatal for the chicks.

Feeding instructions

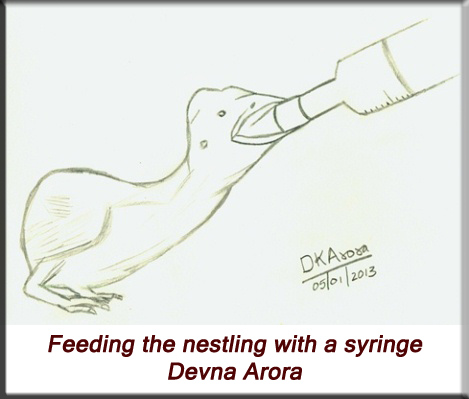

The chick can be placed on a napkin or paper towel on a table so you can feed the chick in a comfortable position – this is vital when feeding the chicks with a syringe. You can also feed the chick when she’s in her basket but all spilled food must be picked up, necessitating the bedding to be changed after feeds.

Our aim is to emulate the parent bird as much as possible when hand-feeding the chicks. Parent birds tap on the chick’s beak to encourage a feeding response. Gently tap the chick’s beak with the feeding instrument in a similar manner to encourage the feeding response. The feeding response is when the chick senses food and gapes, bobbing her head up and down and begging for food. Older chicks also flutter their wings vigorously to attract the attention of the parents when begging for food.

Parent sparrows then feed their chicks by inserting their beaks into the chick’s mouth and dropping the food deep into its mouth. The chicks will only have a couple of morsels at a time. If using a syringe, feed the chicks the equivalents of a couple of bite-sized morsels for that chick. The chick must be given enough time to swallow the first morsel before the second one is offered. There will be a noticeable bulge in the chick’s crop once it has been feed. The crop is a muscular pouch near the throat of the baby bird where excess food is stored for subsequent digestion.

Once the crop is full, not over-extended, and it has had enough to eat, the chick will stop gaping and refuse to open its beak. Feeding must be stopped immediately. The baby must not be forced to feed when it is reluctant to accept food. Force feeding or over feeding can cause the formula or feed to flow into the throat and down its windpipe, which can be life threatening. The beak and feathers of the chick must be wiped gently with a warm, damp cloth after feeding.

Bathing

Sparrows love taking baths, be it water baths or dust baths, as it helps them keep their feathers clean and free of parasites. By the time a chick fledges, it will be eager to take a bath. A bigger, shallow dish of water (preferably mildly warm water if available) must be placed for the chicks during the warmer parts of the day and the chicks will readily hop in. The chicks must be allowed to dry in normal sunlight after their baths.

If housing young birds in an aviary, at least one third of the aviary must be covered in mud or sand so as to allow the chicks to take a dust bath.

Continue to Page 2: growth and corresponding care

Please note: This document is targeted at hand-rearing alone and does not address or substitute any veterinary procedures. For any medical concerns, please consult your veterinarian at the earliest.

For amateurs or people handling new born chicks for the very first time, please keep in touch with a trained and experienced hand for guidance and regular progress updates.

Protocol published in 2013