The House Sparrow Passer domesticus: Nesting, Orphan Care and Rehabilitation, Contd.

Gover Mistry, Devna Arora and Palak Thakor

Link to Page 1: general guidelines

Stage-wise care of house sparrow chicks

N.B. The exact age for the stage may differ depending on the latitude – temperate vs. tropical zones. [Please refer to the note on the previous page for the explanation.]

Stage 1: Nestling – unfeathered

Characteristics: Sparrow chicks are born completely naked with their eyes closed and are completely dependent on their parents for warmth, food and care. Thermoregulation is poorly developed in new-born chicks and they need an external source of heat at all times.

The chicks’ eyes begin to open by the end of the first week. At the same time, the first pin feathers begin to erupt. The feathers, both down and pin feathers, rapidly erupt in the second week of the chick’s life and the chick is adequately feathered by the end of the second week.

Feed: The chicks are extremely delicate at this stage and must only be fed on soft and very easily digestible foods. Cooked rice, moistened biscuits (glucose or marie), mashed boiled eggs – particularly egg yolk, or bread dipped in a little milk are appropriate for chicks of this stage. Baby bird hand-feeding formulas, where available, are also excellent for baby birds. The feed may be rolled into teeny boluses and fed to the chicks with a pair of tweezers or blunt-tipped forceps. The chick’s diet in the first week is primarily carbohydrate-based with roughly 25% of egg yolk.

Alternatively, the chicks could be fed infant cereal formulas like Nestum or Cerelac (Stage 1 or 2 formulas like Rice, Wheat or Wheat and Apple) but this must be done with the help of a feeding syringe. Nonetheless, we recommend that the chicks be given the diet mentioned in the paragraph above and be fed with a pair of tweezers or blunt-tipped forceps.

The chicks do not require any additional water at this stage as they get the required amount through their feed. Giving the chick’s water or liquid feeds (like Cerelac or Nestum – mentioned above) can be particularly dangerous as it can lead to aspiration of the feed if not carefully administered and must be strictly avoided. Water will only be essential for dehydrated chicks that have been in the sun for too long. [Please refer to note on ‘Water and Hydration' in the previous page for further details.]

Many more foods can be introduced to its diet in the second week of the chick’s life, i.e., once the feathers start to develop. The chicks may now also be offered whole-wheat dough, rolled oats or broken wheat porridge (dalia), and moistened cat food in small quantities. Foods such as smooth peanut butter, crushed sunflower hearts or sesame seeds, cake and pancake crumbs, cooked flaked rice (poha) and sprouts may also be introduced in minute quantities to the chicks’ diet. Dough made of sattu or baked/roasted chickpea flour (besan) is an excellent source of protein for the chicks and may be introduced in the second week. Caterpillars (only if you can identify the ones that aren’t toxic!), grasshoppers and crickets may now be added to their diet if you can source some. The proportion of biscuits, soaked bread and cooked rice must be reduced to 50% of the feed in the second week while egg can comprise of 25% of feed and the new introduced foods can make up the remainder of the chick’s feed.

A quarter drop of vitamin drops added to their feeds thrice a day for new-born chicks and half a drop in their feeds thrice a day for week-old chicks should suffice their needs. Calcium supplements and probiotics may be dusted on their feed accordingly.

Feeding quantity and frequency: Feeding must begin at about 6 am and continued late into the night, preferably till 10 pm. The chicks must be fed every half hour. They may consume a couple of morsels at each feed. Once the chick has had enough, it will cease to beg and must then be fed at the next feed. Over-feeding must always be avoided.

Special care: Nestlings require additional warmth throughout the day even when housed at room temperatures. The surrounding temperature must be maintained at 104˚F – 106˚F for the chicks at this stage. Additional warmth will be essential to maintain the temperature once the temperatures dip at night.

Stage 2: Nestling – feathered

Characteristics: Although the chick is adequately feathered by the third week of its life [tropical conditions – chicks in temperate latitudes develop faster], it is yet to develop its flight muscles and primaries (flights feathers) and hence unable to fly at this stage. Chicks develop rather quickly at this stage and will be ready to attempt short flights in another week to ten days. The chicks are quite active and strong by this stage.

Feed: The chicks can now be offered a varied diet. The proportion of moistened biscuit, soaked bread and cooked rice must be reduced to 25% of the feed as it will not give them adequate nutrition. Egg can comprise of 25% of the chick’s diet whereas other food items like whole-wheat dough, sattu or roasted chickpea flour dough, moistened cat food, rolled oats, poha, sprouts, crushed seeds, peanut butter, cake, pancake, caterpillars, etc. can make up the remainder of the diet. New foods like chapattis, bird cereal mixes, breakfast cereal mixes and crushed, soft nuts like cashews may also be introduced to the chick’s diet. Infant cereal formulas, if given previously, will no longer be necessary. A drop of vitamin drops and some calcium and probiotics may be added to the chick’s meals thrice a day.

Syringe feeding, if it has been attempted, will be absolutely un-necessary at this stage. Chicks at this stage must be fed using a pair of tweezers or blunt-tipped forceps. Shallow bowls of water must be available for the chicks as they may now attempt to drink water.

Feeding quantity and frequency: The chicks must be fed every half hour to forty-five minutes as they will now be able to consume larger quantities in one go. Feeding must begin by 6-7 am and continued at least until 8-9 pm.

Special care: External heat may be discontinued during the day on warmer days or depending upon the environmental conditions where you live but may be required at night. The surrounding temperature may now be maintained at 102˚F – 104˚F for the chicks at this stage. Thermoregulation also develops by this age and as the chicks are now also feathered, they retain heat a lot better.

Stage 3: Fledgling – dependent upon parents

Characteristics: The chicks fledge by the time they are less than 3 weeks old in temperate countries or a roughly 25 days old in tropical countries.

Feed: The chicks will now eat almost everything that adult sparrows eat. Moistened biscuits, soaked bread, peanut butter may now be completely discontinued. Their diet will now comprise of cooked rice, boiled egg, sprouts, chapattis, crushed nuts and seeds, whole-wheat dough, sattu or roasted chickpea flour dough and rolled oats.

The chicks must not be hand-fed with raw grains like millet (jowar, bajra), rice, soaked pulses and other bird seed mixes. These must be left scattered on the floor for the chicks to pick them themselves. This will prevent forcing hard to digest foods on the chicks if they are not ready for it.

Feeding quantity and frequency: The chicks begin to start feeding on their own at this stage. They may now be hand-fed every hour to encourage them to feed on their own if they get hungry sooner. Feed must be available for them in small, shallow dishes at all times as they will attempt to pick a few morsels by themselves.

Special care: The chicks will not require any external heat at this stage but must be given warm roosting spaces nonetheless. If deemed necessary, they may be kept in temperature-controlled boxes at 102˚F.

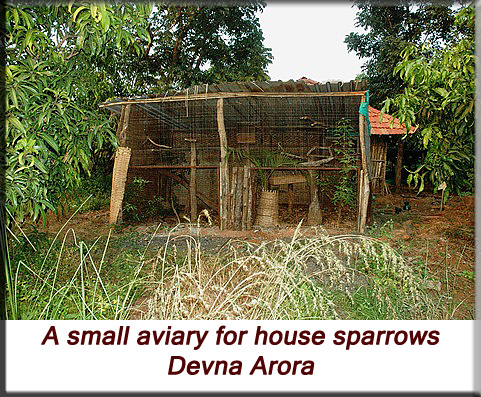

The chicks must be shifted to an aviary at this stage as they need flight practice before release. The aviaries must have adequate nest boxes for the chicks as they will prefer to roost in the boxes at night. The rehabilitation process must also now begin.

Two bowls of water must now be available for the chicks at all times: one large, shallow dish for the chicks to bathe in and a smaller shallow dish with drinking water. The chicks often jump into both the bowls and soil the drinking water as well which necessitates a change of fresh water every couple of hours.

Stage 4: Fledgling – independent

Characteristics: The chicks are now completely independent and must be readied for release. The process of soft release begins.

Feeding: The chicks will now consume an adult diet and must be given an assortment of foods. The chicks should be completely independent and feed on their own by this age. Fresh food and water must be available for them at all times.

Stage 5: Sub-adult/Immature

Their feathers are fully grown and adult plumage starts to appear. The male birds now begin to get the characteristic crown and bib. The colour of the beak is also an indication of maturity. At this stage, the yellowness to the base of the beak completely fades; yet, the beak is not the characteristic adult colour yet.

The chicks must have been released by this stage. If opting for a hard release, this is the right time to release them.

Stage 6: Adult birds

Adult sparrows will be completely independent, may have integrated with flocks of wild sparrows and should have completely stopped returning to the aviary. They will breed in the following season.

Rehabilitation and Release

The young birds must be must be shifted to an aviary at the time of fledging and given adequate flight exercise before release. This is essential for them to develop the agility and swiftness required for survival. The aviary must be at least partially sheltered so the birds are not exposed to harsh sunlight throughout the day. Food at this stage must not be offered in one place but scattered around throughout the day so the young birds learn to search for it. Ultraviolet lights may be placed just outside the aviary to attract insects in the evenings – this will get the chicks accustomed to looking for and chasing after flying insects. Care must be taken to prevent the chicks from flying into the mesh and injuring themselves. Fresh drinking water and a larger shallow bowl of water to bathe in must be available at all times. The aviary must also have a couple of nest boxes, hung higher in the aviary, for the young birds to roost in.

The first step towards getting your bird ready for release is for it to go through a conscious process of rehabilitation. This process is to break the young bird’s dependency on human beings and to give it maximum opportunities to be tuned in to its natural instincts. The process of rehabilitation must actively start by the time the chick is ready to fledge and followed meticulously until release.

House sparrows are social birds and only live in flocks, or ‘hosts’ as they are called. Flock size may vary greatly with local environmental conditions and the availability of resources. An important consideration when releasing hand-raised young is to remember that house sparrows do not exit alone and must only be release where and when they can join wild sparrows. Sparrows are dependent on the safety and protection of the rest of the flock while young sparrows also benefit from the guidance of more experienced birds. For the similar reasons, it may be advisable to bunch young birds from various facilities or individuals and group them together prior to release. This in turn will increase the survival chances of each of the birds.

Important things to be kept in mind when releasing sparrows includes,

1. Place of release, possibility of reunion with existing flock and the prevailing environmental conditions

Wherever possible, all rescued animals must be released where they have been picked up from. This is particularly important when releasing animals that had been admitted to care centres as adults as they will again have the chance to unite with their own groups and flocks. Younger birds must be released in suitable locations where they have maximum chances of integrating with wild sparrows and in locations where they will be easy to monitor for the first few days after release.

The only instance where release to the same location must be avoided is if there have been irreversible changes which led to the initial displacement of the birds in the first place and will have rendered the place unsuitable for the survival of the species.

2. Age and timing of release

Birds that have been admitted as sub-adults or adults may be released just as soon as they are ready to be released. The only consideration for them is fitness for survival.

Birds that have hand-raised, on the other hand, need to go through a more protective method of release. Young birds may be released at the age of about 2 months when opting for a soft release whereas those that are being hard released must only be released after 3 months of age.

3. Method of release

Birds may be released by following protocols for either a soft release, which is most ideal and recommended for hand-raised young, or through a hard release.

Hard Release is a means by which the animal is released into a new location without its being accustomed to the new environment. This process is appropriate for sparrows that have been taken into care as adults.

Soft Release is a means by which the animal is gradually introduced or familiarized to a new environment before its release into that location. Hand-raised animals are at a disadvantage of not having had adequate parental learning and require additional safety and protection during release; hence the ideal way to release them is through a process of soft release.

The simplest way to soft release a sparrow is by allowing it to fly in-and-out of its enclosure for the first few weeks after it fledges and becomes fairly independent. The young must be shifted to enclosures where they will be released from so that they can identify the enclosure and their surroundings as this will help in building site fidelity and make it easier for them to return to the safety of the enclosure until they are completely independent and ready to leave. The young birds may be allowed to fly out in a few weeks thereafter through a couple of openings/windows in their enclosures. At this age, the birds will not fly far and return to their enclosure several times during the day and most certainly to roost at night. The access opening and windows must only be opened at dawn and closed at night to prevent entry of predators like rats, cats, snakes, etc.

Once they have explored their surroundings and have found safe roosting spaces for themselves, they will cease to return to the protection of their aviary but may return for titbits of food. Eventually, they will become completely independent and case to return to the aviary at all. Supplemental feeding must be continued until the birds are independent but may be ceased once the birds are self-sufficient.

Attracting wild sparrows to the aviary will be of particular advantage to the young. A simple way of doing this is to ensure that the aviary is close to free ranging wild sparrows and then strewing grain in and around the aviary. This will bring wild birds closer in contact with the young and expose them to wild birds and their behaviours. This will also facilitate grouping with the wild birds once the youngsters have been released.

Birds may be released in a similar manner if hand-raising and releasing from home. They must have a room to themselves to fly about in and access to a window which attracts wild sparrows. Experience suggests that birds released from homes return for longer durations as they may have stronger bonds with both the homes and the caregivers. They are also known to visit every now and then well after the gain complete independence.

Note of caution: A ceiling fan must never be used in a room with birds to ensure they don’t fly into a moving fan and get injured fatally.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aaron, Alistair, Andrey, Debbie, Kate, Gaurav and Paul for their good wishes and the permissions to use their photographs. Thank you!

Authors

Gover Mistry

Teacher of Sciences (Retd.) and Avid Bird Enthusiast,

Bred and observed wild sparrows for two decades,

Pune, India

Devna Arora

Wildlife Biologist and Rehabilitator,

Author and Founder of Rehabber’s Den,

Pune, India

Palak Thakor

Educator and Wild bird Rescue Coordinator,

Prayas – Team Environment,

Surat, India

For any further details or suggestions, please contact us at Rehabber’s Den: devna@rehabbersden.org

Purchasing baby bird hand-rearing formulas

Hagen: Tropican baby hand-feeding formula

http://uk.hagen.com/Bird/Nutrition/Extruded/B2261

http://www.hagen.com/hari/docu/trophfad.html

Kaytee: Exact hand feeding baby bird

http://www.kaytee.com/products/exact-hand-feeding-baby-bird.php

Photographs used

Aaron – Fledged sparrow being fed by the male

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/61657236@N04/6983038540/sizes/k/

in/photostream/ [Accessed – 05/01/2013]

Alistair – Pin feathers erupting in the second week

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ebothy/5978510709/sizes/o/in/set-72157627287805486/ [Accessed – 03/01/2013]

Alistair – Feathered nestling

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ebothy/5987237328/in/set-72157627287805486/ [Accessed – 03/01/2013]

Andrey – House sparrows bathing

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/akras/2748850187/in/set-72157604344418373/ [Accessed: 05/01/2013]

Debbie Cooper – Independent fledgling

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/snowbabies/3565403411/sizes/l/in/

photostream/ [Accessed: 05/01/2013]

Dr. Kate Vincent – 5 day old chick

Available from: http://housesparrow.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/5_day_old_house_sparrow_chick.jpg[Accessed: 03/01/2013]

Gaurav Kavathekar – Naked nestling begging for food

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/gdkpics/7063714501/in/photostream/[Accessed: 03/01/2013]

Paul Hillman – Dependent fledgling

Available from:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/36543276@N02/7354298586/[Accessed: 03/01/2013]

References

BTO (no date) House Sparrow Passer domesticus

Available from: http://blx1.bto.org/birdfacts/results/bob15910.htm

[Accessed: 20/12/12]

Bet (2012) House sparrow biology

Available from: http://www.sialis.org/hospbio.htm[Accessed: 10/10/12]

Bouglouan, N. (no date) House sparrow

Available from: http://www.oiseaux-birds.com/card-house-sparrow.html [Accessed: 10/10/12]

Brzek et. al. (2009) Developmental adjustments of house sparrow (Passer domesticus) nestlings to diet composition

Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19376949[Accessed: 16/10/12]

Butchart, S. and Symes, A. (2012) Passer domesticus

Available from: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/106008367/0[Accessed: 19/12/12]

Ehrlich, P.R., Dobkin, D.S. and Wheye, D. (1998) Metabolism. Stanford University. Available from:

http://www.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/

Metabolism.html [Accessed: 29/12/2012]

Everyday Enchantment (2011) Baby sparrow rescue

Available from: http://www.nordinfarms.com/blog/?page_id=2403 [Accessed: 10/10/12]

Flammer, K. and Clubb, S. (1994) Neonatology in Ritchie, B.W., Harrison, G.J. and Harrison, L.R. (1994) Avian Medicine: Principles and Application

Available from:

http://www.harrisonsbirdfoods.com/avmed/ampa.html[Accessed: 04/01/13]

Gage, L. J. and Duerr, R. S. (2007) Hand-rearing birds. Blackwell Publishing, Iowa, USA

Grodzinski, U. (2008) Adaptive and process-based explanations in the study of parent-offspring communication: Experiments with hand-raised house sparrow nestlings and game theoretical modelling

Available from:

http://www.zoo.cam.ac.uk/zoostaff/madingley/library/member_papers/

ugrodzinski/Uri_Grodzinski_PhD.pdf [Accessed: 10/10/12]

McNab, B. (1965) An analysis of the body temperatures of birds. Department of Zoology, University of Florida.

Available from: http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v068n01/p0047-p0055.pdf [Accessed: 29/12/2012]

Oates, E.W. (1890) The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma: Birds – Vol. II, Taylor and Francis, London

RSPB (2011) House Sparrow: Population trends

Available from:

http://www.rspb.org.uk/wildlife/birdguide/name/h/housesparrow/

population_trends_and_conservation.aspx [Accessed: 20/12/12]

Ritchison, G. (undated) Avian energy balance and thermoregulation. Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University

Available from: http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/birdmetabolism.html[Accessed: 29/12/2012]

Stocker, L. (2005) Practical wildlife care (Second Ed.). Blackwell Publishing

Summers-Smith, J.D. (no date) Decline of the House Sparrow: A review. Newbury District Ornithological Club

Available from:

http://www.ndoc.org.uk/articles/Decline%20of%20the%20House%20

Sparrow.pdf [Accessed: 20/12/12]

Vincent, K. (2005) Study into urban house sparrow depletion in the UK

Available from: http://www.katevincent.org/ [Accessed: 20/12/12]

Vriends, M. M. (1996) Hand-feeding and raising baby birds, Barron’s Educational Series, Inc.

Wildlife Hotine (2012) Raising baby sparrows and starlings

Available from: http://www.wildlifehotline.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/NonNative-Birds-How-To.pdf [Accessed: 10/10/12]

Further Reading

Bet (2012) Managing house sparrows

Available from: http://www.sialis.org/hosp.htm[Accessed: 10/10/12]

Brzek et. al. (2011) Fully reversible phenotypic plasticity of digestive physiology in young house sparrows: lack of long-term effect of early diet composition. Available from:

http://jeb.biologists.org/content/214/16/2755.full.pdf+html[Accessed: 10/10/12]

Fitzwater, W.D. (1994) House Sparrows

Available from:

http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/nreos/wild/pdf/wildlife/HOUSE_SPARROWS.PDF[Accessed: 16/10/12]

Gionfriddo, J.P. and Best. L.B. (1995) Grit use by house sparrows: effects of diet and grit size

Available from:

http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v097n01/p0057-p0067.pdf [Accessed: 16/10/12]

Grodzinski, U. and Lotem, A. (2007) The adaptive value of parental responsiveness to nestling begging

Available form:

http://www.tau.ac.il/~lotem/pdf/Grodzinski%20%20Lotem%202007

%20reprint.pdf [Accessed: 10/10/12]

Grodzinski et. al. (2009) The role of feeding regularity and nestling digestive efficiency in parent-offspring communication: an experimental test. Available from:

http://ibis.tau.ac.il/twiki/pub/Zoology/Lotem/PublicationsList/Grodzinski

etalFE2009.pdf [Accessed: 10/10/12]

Katsnelson et. al. (2010) Individual-learning ability predicts social-foraging in house sparrows

Available from:

http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2010/08/27/rspb.

2010.1151.full.pdf [Accessed: 10/10/12]

NABS (2012) House sparrow control. Available from:

http://www.nabluebirdsociety.org/PDF/FAQ/NABS%20factsheet%20-%20HOSP%20Control%20-%2024May12%

20DRAFT.pdf [Accessed: 10/10/12]

Excellent photographic progress of the growth and development of house sparrows

Photographs by Susan and David on Jackie Collin’s Starling Talk

Growing up – Sparrow photo album 1

http://www.starlingtalk.com/growingup_album1.htm

Growing up – sparrow photo album 2

http://www.starlingtalk.com/growingup_album2.htm

Links to videos

Feeding Jack Sparrow

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OCutT57cr0

Female house sparrow feeding babies

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGZAw09xy6c

Hand feeding house sparrows

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZskaxmYGRY

Peanut – the rescued house sparrow

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1aT_fPPK-Y

Spoggy the sparrow – raising a 1 day old baby bird

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MovUzO_cpA

Please note: This document is targeted at hand-rearing alone and does not address or substitute any veterinary procedures. For any medical concerns, please consult your veterinarian at the earliest.

For amateurs or people handling new born chicks for the very first time, please keep in touch with a trained and experienced hand for guidance and regular progress updates.

Protocol published in 2013